An anonymous Court Watch volunteer reports on the Allegheny County Jail’s deeply troubling new contracts

If you didn’t know better, you might think STL Joseph Garcia is a Navy SEAL. That’s certainly the look he and his business, Corrections Special Applications Unit (C-SAU), are going for.

Joseph Garcia’s Facebook profile shows him posing in front of a helicopter with a gun slung across his chest and a pit bull at his feet. His personal Instagram account offers an array of pictures of himself looking tough, for example leaning casually against a brick wall dressed in a tight shirt tucked into blue jeans, flanked by a pair of Giant Schnauzers. He describes himself (and his K9s) as “battle-tested,” and the honorific “STL” could lead a person to believe that he’s attained some kind of military rank.

But as official as it sounds, I haven’t been able to figure out what STL stands for–perhaps “Strike Team Leader”? But in fact, no one seems to know of any particular qualifications Joseph Garcia might have. When his training methods caused a scandal at Rikers, he disappeared. When a court solicitor investigated him, she quickly found that “his credibility is in question.” In a civil suit filed last year against a Colorado jail, the plaintiff alleged that Garcia uses “a variety of shell companies” to do business. His business, by the way, is developing “new and different approaches to handling inmate riots.“

Put bluntly, he is a charlatan who specializes in teaching prison guards to shoot incarcerated people with 12-gauge shotguns at close range. And none of that stopped Allegheny County, Pennsylvania from giving Mr. Garcia almost $350,000 to pay a visit to our county jail.

Charleston County, South Carolina

In December 2009, the Charleston Post and Courier ran a story on a training at the Charleston County Detention Center. The Detention Center, also known as the Sheriff Al Cannon Detention Center (SACDC), had invited a corrections expert to help bring the jail into the 21st century. This expert, “Lieutenant” Joseph Garcia, is described in the piece as the “lead instructor for U.S. Corrections, a government contractor.”

Garcia tells the reporter about one of the compliance techniques he teaches in his classes: pointing a “less lethal” shotgun at an incarcerated person while blinding them with a laser pointer. He teaches that if an incarcerated person remains noncompliant after being blinded, the officer should load the shotgun. “Once we do that, the inmate knows we are not playing,” Garcia says. If that still doesn’t work, the officer should simply shoot the incarcerated person with rubber rounds “until the pain convinces them to comply.”

The reporter observes wryly that thanks to this state of the art training, any “unruly inmates” at the jail are sure to be “greeted by a new kind of correctional officer, one who can be very persuasive.”

In May 2015, another story appeared in local Charleston media about an exciting new training at SACDC led by Joseph Garcia. The reporter seems under the impression, troublingly, that Mr. Garcia’s company (operating at this point as US Corrections Special Operations Group, or US C-SOG) is a “government based agency.” She tells us breathlessly that Garcia’s program is “the gold standard in the corrections special operations community” and refers to Garcia as “Captain,” though neither the Post and Courier nor herself elaborate on any kind of military experience he may have. Both note that Garcia is based out of Virginia, gently suggesting affiliation with the federal government.

But Mr. Garcia is not a government employee, nor does he appear to have served in the military. And as of January 5th, 2021, his “persuasive” methods have contributed to at least one death.

Jamal Sutherland

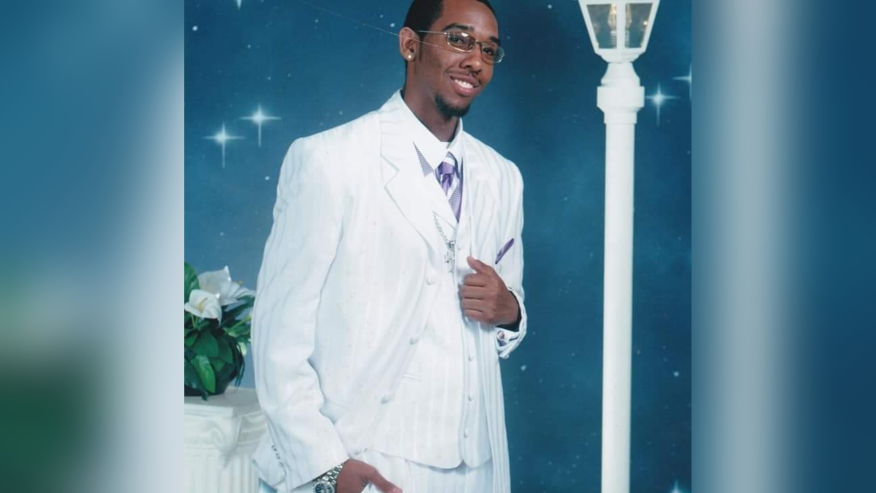

Photo of Jamal Sutherland, provided to media by his family

On January 5 of this year, a young man named Jamal Sutherland was killed by corrections officers at SACDC. Mr. Sutherland was 31 years old and had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He sometimes experienced visual and auditory hallucinations and was attempting to cope with these symptoms when he checked himself into a psychiatric hospital on New Year’s Eve. He was arrested at the hospital less than a week later when he tried to break up a fight between two other patients. Even though Sutherland had not participated in the fight himself, and even though medical staff knew that he was struggling with psychotic hallucinations and delusions, the facility chose to call the police and have him taken to jail. As this thoughtful piece puts it simply: “He died trying to get help.”

On May 14th, a little over five months after Sutherland’s death, the body cam footage of his death was made available to the public. I have not watched it and I will not post it here, but be aware that most stories on his death have the video embedded. Here is a description of the video from the Associated Press:

“In newly released video of the January death of a South Carolina inmate with a history of mental health issues, deputies are seen deploying stun guns repeatedly and kneeling on the man’s neck and back before he stops moving.”

On May 18th, following renewed public outcry and multiple protests, the Solicitor for South Carolina’s Ninth Circuit assured the public that her Office was hard at work conducting an investigation. She added that she herself had been haunted by the body cam footage since seeing it shortly after Sutherland’s death– “I have lived with its sights and sounds for months.” A week later the city of Charleston paid out a $10 million dollar settlement to Jamal Sutherland’s family. Finally, on July 26th, the Solicitor’s Office released the results of their months-long investigation.

They found that Joseph Garcia’s training directly contributed to Sutherland’s death.

The Reports

There are two reports: the official Ninth Circuit Solicitor Office’s Report and The Raney Report, a Use of Force Analysis commissioned by the Solicitor’s Office.

From the Solicitor’s Office report:

- “[Joseph] Garcia conducted the SACDC Special Operations Group (SOG) training from around 2008 through 2019” and “much of the substance of what Garcia taught is still used to train SOG operatives”

- In first hiring Garcia and then continuing to use his methods, SACDC leadership “sanctioned training that preferred the use of force over avoidance and de-escalation techniques”

- The officers that killed Mr. Sutherland “were negligent but they also complied with much of their training,” and so, accordingly “training at the detention center must change.” (emphasis mine)

The Raney Report, written by a former Sheriff named Gary Raney, declines to name Joseph Garcia outright but there is no doubt to whom it refers in describing a “vendor who taught highly aggressive tactics.”

- In 2008, the jail “contracted with a private vendor, to redesign the training and tactics for the SACDC tactical response team”

- “The vendor began teaching aggressive tactics, emphasizing the use of weapons and physical force”

- The SACDC “adopted a practice, unheard of in most jails, that the SOG members routinely carried tactical 12- gauge shotguns loaded with less lethal munitions, regardless of whether there was an immediate need for them or not.”

- “There was no evidence of meaningful de-escalation or avoidance training in the SOG training”

- “SACDC sanctioned and continued rogue practices with the SOG training and failed to address policy violations and poor practices. This is indefensible and a fundamental cause of why the events unfolded prior to Sutherland’s death.” (emphasis mine)

These reports confirm Garcia and SACDC’s consistent pattern of sadistic violence against incarcerated people (to say nothing of his bilking of prison administrations) stretching from Rikers Island to Weld, Colorado to York County, Pennsylvania–and now to Allegheny County.

Allegheny County

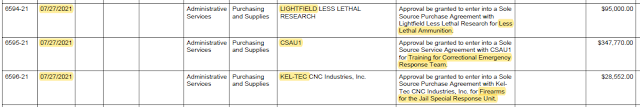

As Sheriff Raney and the Ninth Circuit Solicitor’s Office were finalizing their reports, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania was approving a contract worth hundreds of thousands of dollars to bring Garcia’s training methods to ACJ. There would be no opportune moment for a visit from Mr. Garcia, but the timing of this purchase is deeply troubling.

At last month’s Jail Oversight Board meeting, ACJ’s Warden Orlando Harper was asked to explain his plan to implement the jail-related ballot initiative that passed in May. He snapped that the changes will take time because the new law removes some of the Jail’s most important “tools” from their “toolbox.”

The initiative’s central feature is that it bans the use of solitary confinement, but it contains another really important provision: It bans the use of restraint chairs, chemical agents, and leg shackles within the Jail.

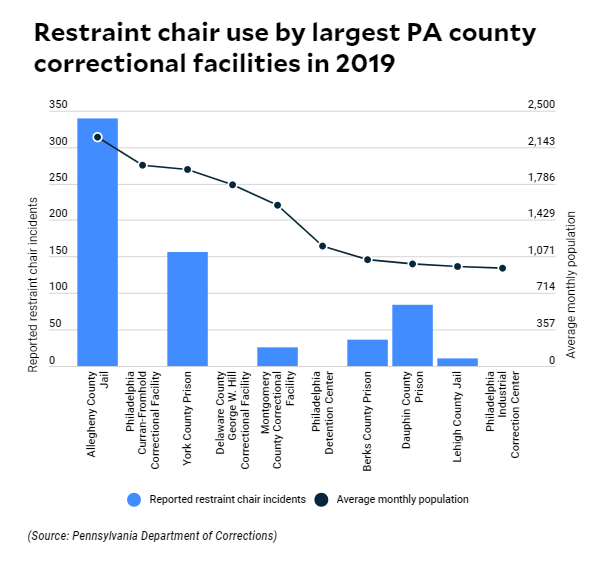

Allegheny County Jail is one of the least transparent in the state, but what little information manages to escape its walls is often shocking– For example, the fact that ACJ subjected incarcerated people to the restraint chair on 339 separate occasions in 2019. Warden Harper and his staff have demonstrated a willingness to use the restraint chair and other forms of inflicting severe pain at a rate that far exceeds every other jail in the Commonwealth.

So why hire Garcia now? The Jail will no longer be able to (legally) mace inmates in the face and strap them into the chair for 12 hours, and Harper is scrambling to find new ways to terrorize ACJ’s “residents.”

“De-Escalation”

The $347,770.00 C-SAU training isn’t the only ask Warden Harper made to the County. The request for Garcia’s services came accompanied by requests for $28,552 of Kel-Tec firearms and $95,000 worth of Lightfield “less lethal” ammunition.

The County is taking away the pepper spray, so the Warden is buying bullets.

County Councilperson Bethany Hallam asked the Warden about these contracts at the August meeting of the Jail Oversight Board. She reminded him that earlier in that very meeting, Board Members Moss, Korinski, and herself had proposed contracting with a “de-escalation education” firm called Verbal Judo to train staff. Seemingly caught off-guard by Hallam’s familiarity with the contracts, Harper made the dubious claim that C-SAU would also teach de-escalation tactics.

This begged the question (voiced by an incredulous Hallam): “Your plan is to use shotguns and bean bags to de-escalate?”

The Warden declined to comment further.

Frank Smart

Just after midnight on January 5, 2015, a man named Frank Smart, Jr. was declared dead at Pittsburgh’s UPMC Mercy Hospital. In much the same way that Sutherland would be killed exactly six years later, Smart was physically restrained by corrections officers who refused to recognize (or simply did not care) that he was in crisis.

Smart had a seizure disorder and was prescribed a twice-daily medication to manage it, but the medical staff provided by for-profit healthcare provider Corizon Health failed to give it to him. He was arrested on the morning of January 4th and was stricken with a grand mal seizure sometime in the afternoon, falling to the ground in his cell and hitting his head twice.

Corrections officers did not notice his distress until the seizure was already ending and Smart was transitioning into the postictal state. As he regained awareness and tried to re-orient himself, the officers who had come to check on him perceived his behavior as threatening. Some of them apparently believed that even as he lay on the floor of his cell, blood at the corners of his mouth, his movements indicated that was trying to assault them. Officers shackled him and “restrained” him, placing him in a chokehold and kneeling on his body.

Like Jamal Sutherland (and Eric Garner, and George Floyd, and so many other Black men murdered by law enforcement officers), some of Frank Smart, Jr.’s last words were “I can’t breathe.”

Allegheny County Jail does not need any help figuring out how to be “persuasive,” or whatever euphemism one prefers in place of cruel or vicious.

We cannot give these sadists shotguns. People will die.