Violence work, occupation, and apartheid in Allegheny County

by Suhail Gharaibeh

Content warning: anti-Black hate speech; gun violence

It’s all on video. Just after 4:15 on the afternoon of Sunday, December 20th, 2020, closed-circuit television captures a white police SUV pulling into the rear entrance of the McKeesport Police station between Blackberry and Market Streets. On the right of the frame we can see snow on the ground, and snow on the train tracks that separate the police station and McKeesport’s main drag from the hulking Dura-Bond Pipe facility on the south bank of the Monongahela River.

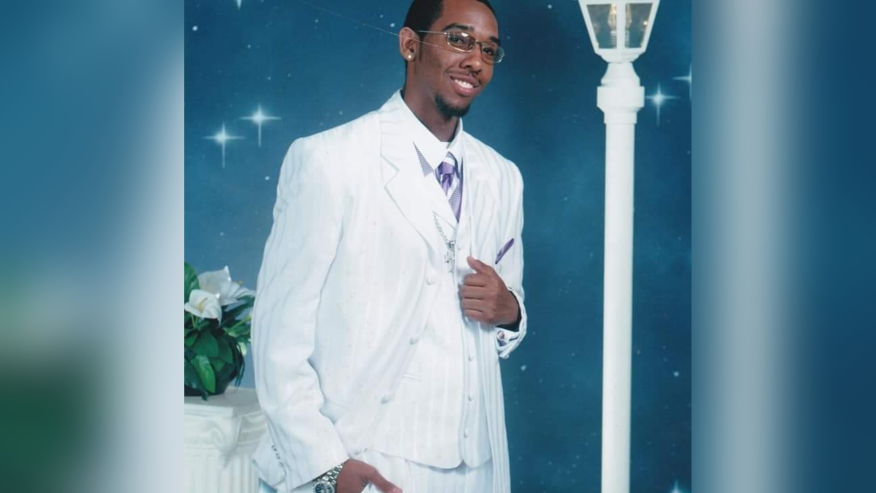

The cruiser parks, and an officer (later identified as Gerasimos “Jerry” Athans, 32) exits the driver’s side and walks around to open the back right door. Suddenly Athans stumbles back, stunned, (we’d learn later he’d been shot in the neck and shoulder, spots left uncovered by his ballistic vest) and moves behind the hood of the cruiser. A man in a black hoodie (later identified as Koby Lee Francis, 22) exits the backseat and points his arms toward Athans, presumably shooting at him once more, before running east, away from the station and out of the frame, ducking to avoid Athans’ returning shots. (We’d learn later that Francis fled McKeesport at some point after this, and Athans was flown to UPMC Presbyterian in Oakland to be treated for wounds to his neck and shoulder.)

This is the entirety of the released footage. There’s no audio, just a thirty-second clip of video. It’s exactly the sort of scene that our televisual mass culture loves to latch onto: a single moment of shocking violence, immortalized by a fly-on-the-wall camera. The story was broken by several local reporters and the accompanying footage was rapidly released on social media, including via the official Twitter accounts of the Allegheny County District Attorney and the US Marshals Service.

Unsurprisingly, the video clip of a Black male suspect shooting a white policeman rapidly became the story in itself among right-wing and pro-police social media circles. Under a tweet from KDKA, one user posted a YouTube link to his own electric guitar cover of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which he dedicated to Officer Athans. “Back the Blue,” “Blue Lives Matter,” and “Thin Blue Line” stock images began popping up on posts about the shooting. Racist jokes about absentee fathers abounded. Under a photograph of Francis tweeted by KDKA, one user wrote, “No graduation pic!!?? Dindu Nuffin, better call Crump.” Three BLM-era tropes are rehashed here—the mocking allusion to the media’s use of graduation photos when covering victims of police brutality like Michael Brown, Jr.; the use of racist moniker “Dindu Nuffin,” a neologism derived from the AAVE “didn’t do nothing”; and the reference to Black civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump, who has famously represented victims of racist murder from Trayvon Martin to Jacob Blake. Echoing the nineteenth- and twentieth-century zeal for lynching, other users called for Francis’ summary execution: “Black lives don’t matter with this one! Put him down!” wrote one. “Give him the needle,” commanded another. “And that my friends is what we call a rabid animal,” wrote a third. “You act like one, you get taken down like one. Hope the officer is OK.”

It’s no coincidence that all these tropes are deeply anti-Black and deeply pro-police. We know now that throughout American history, white supremacy has convened under the auspices of “law and order.” Just look at the number of rioters at the Capitol on January 6th who belong to police and military units from across the country. White supremacists (who, as it so happens, need not be white themselves) act as self-declared crusaders against “Black criminality” (an ideological construct, they refuse to acknowledge, that has been built by and for white supremacy).

Not all the responses to Athans’ shooting were virulently and explicitly anti-Black. But even the most benevolent both-sides-ism (“police are scared, too!”) is deeply misleading because it smudges away all the context that surrounds interactions between police and civilians. As abolitionists, we must grapple with the fact that Francis and Athans were entangled in a much broader relationship of power and authority than what is visible in those thirty seconds of CCTV footage.

The video of the shootout is sensational and upsetting. It was an “easy A” for some local reporters—you get a story you can follow, neatly reported by the police; you publish it, and you get to watch as the public swarms to it and picks it apart for meaning, bringing you ad revenue and social-media clicks. But it’s not actually very substantive. Simply viewing and reviewing this highly-clickable video doesn’t actually tell us much about what we’re seeing. And it certainly doesn’t constitute critique.

Why did this violent event occur? How did two young men living and working in the same community—one a white, 32-year-old cop; the other a Black, 22-year-old civilian—end up in a nearly-deadly shootout? The dominant mode of thinking (as exemplified by the Twitter users above) tells us that this all occurred because Black people are inherently prone to criminality, and instinctively attracted to violence. This explanation, of course, is pure ideology. It’s less connected with reality than it is with the white supremacist and anti-Black ethos of the American state project in general, and of the carceral apartheid regime of Allegheny County in particular.

In order to truly understand that moment on December 20th, 2020, let’s rewind.

September 2016. A former Pitcairn Police and current McKeesport Police officer, Melissa Adamson, a white woman, was fired after posting a Snapchat photo of herself in uniform with the caption, “I’m the law today nigga.” The firing (somewhat surprisingly) got reported by national and international newsrooms, and became a local cause célèbre. That Adamson ever thought this Snapchat selfie was a good idea says a lot about the types of people working in Allegheny County’s municipal police departments (PDs). Koby Francis was high-school age at the time, in a school district with double-digit racial achievement gaps and a superintendent who had to be threatened with federal legal action by the ACLU before he would allow students at McKeesport Area High School to form a Black Student Union. (The superintendent told reporters that “he grew wary of the initiative…[once] it became apparent that local activist and McKeesport mayoral candidate Fawn Walker-Montgomery was behind the effort.”)

November 2017. Koby Francis was 19 years old. He and another 19-year-old from McKeesport named Savonce Williams were facing a battery of charges after an alleged October 24th robbery. They were both held for court on $5,000 bail by Magisterial District Judge Eugene Riazzi—himself a former McKeesport Police Detective. Apparently unable to post bail, Francis was held in the Allegheny County Jail instead.

In summer 2018, Francis pled guilty to the charge of criminal conspiracy and was sentenced to three years’ probation by Common Pleas Judge Donna Jo McDaniel. This process left Francis with over $4,000 in court fees, according to his criminal docket. Here’s the October 24th, 2017 event that led to Williams and Francis being arrested in the first place, according to Mon Valley paper The Tube City Almanac: “McKeesport police said that an Abraham Street resident reported that two men visited her home to ask about an apartment for rent. When they left the house, she noticed a video game console was missing. She confronted them as they got back into their car, police said, but the men drove away, knocking her to the ground.”

What would it look like if this dispute had been settled according to the principles of transformative justice, rather than punishment and retribution? What if Francis and Williams had been charged with the simple task of replacing the Abraham Street woman’s video game console? What if the woman, accompanied by a social worker, had been able to sit down Francis and Williams and tell them, face-to-face, how they hurt her?

In early December 2018, Judge Donna Jo McDaniel, who had sentenced Francis in this case, resigned amid accusations of bias and sanctions by the Pennsylvania Superior Court.

The very same week, Koby Francis was arrested again as part of a massive drug sweep that local police had reportedly been planning for over half a year. At just 20 years old now, Koby was one of the youngest arrestees in a sweep that ended in charges being filed against 70 residents of Allegheny County.

Francis was assigned Judge Jeffrey Alan Manning in the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas. Manning has a judicial history that can only be described as sordid. He’s known for his commanding personality, raucous outbursts, and cigar-smoking. Among Black Allegheny County residents and activists, Judge Manning is notorious for upholding white supremacy in his courtroom; among women attorneys, he is notorious for his misogyny. In April 1998, Manning was brought before Pennsylvania’s Court of Judicial Discipline for allegedly having referred to two Black women as “nigger[s]” on two separate occasions. In 1999, the Allegheny County Bar Association refused to recommend Manning for retention, citing, in part, his sexism as perceived by female lawyers and judges. “Those who know him best say he is a sexist,” wrote the Post-Gazette in 2001. In 2007, Manning faced a federal investigation by the FBI and IRS after allegedly giving special treatment to long-time friends of his, particularly criminal defense lawyer Patrick Thomassey, with whom Manning worked as a teenager at a local country club. No charges were ultimately filed. In 2008, he cleared the now-infamous Pittsburgh Police officer Paul Abel of all charges related to an incident in which Abel’s gun went off as he drunkenly pistol-whipped a twenty-year-old man on the South Side, shooting him through the hand. Manning’s decision allowed Abel to continue working (until 2020, when he was fired, unsurprisingly, for excessive force). In 2015, Manning “broke a legal norm” by accepting a lenient plea deal that offered probation to three of five white men who ganged up on a Black man and threw him onto the train tracks at the Wood Street T station after a Kenny Chesney concert. Manning told reporters he “felt compelled to accept” the deal. After all of this, in 2018, protestors demanded that Manning be removed from the trial of East Pittsburgh Police officer Michael Rosfeld, who shot 17-year-old Antwon Rose, Jr. three times in the back as he ran away from Rosfeld. Rosfeld was to be represented in Manning’s court by none other than attorney Patrick Thomassey.

This 2018 trial in the court of Judge Manning again left Francis with thousands of dollars in legal fees. It’s unclear which controlled substances Francis was accused of being involved with. In any case this sweep was conducted in a day and age where the War on Drugs has been declared an abject failure, and policy experts around the world are urging against criminalization and incarceration as a response to drug trafficking. This War-on-Drugs-era sweep is exactly the type of police offensive that resulted in the murder of Breonna Taylor in March 2020 (and so many others).

Again, as abolitionists, we must ask the question, no matter how kooky it may seem in the eyes of our opponents to the right: what would Koby Francis’ life be like today if the hair-trigger reaction was not to incarcerate him for being involved in drug dealing, but rather to give him the support needed to transform and heal his life?

For Black American men like Koby Francis, the likelihood of being incarcerated within one’s lifetime is one in three (compared to one in seventeen for white men). Black adults, while representing just 12 percent of the US’ population, make up 33 percent of the US’ prison population (which, in turn, is the largest group of incarcerees on the planet). Black people are disproportionately likely to be arrested and incarcerated for drug-related offenses, despite using drugs at the same rate as all other races.

This reality of carceral apartheid only gets clearer when we zoom in on a place like Allegheny County, one of the most deeply segregated metropolitan areas in the country. It’s one of many American metro areas that serve as touchpoints for the prison-industrial complex, with the carceral geography of Greater Pittsburgh culling scores of oppressed and exploited people—largely members of the Black working class—into its dangerous machinery.

Recent research by ALC has borne this out. The new report “Apartheid Policing in Pittsburgh: Why Defunding the Police Can’t Wait” details how, in 2019, Black people made up only 23.2 percent of the Pittsburgh population, and yet they made up 43.6 percent of individuals involved in traffic stops, 71.4 percent of all frisks, 69 percent of individuals subject to warrantless search and seizures, 63 percent of all arrests conducted by the Pittsburgh Police, and 60 percent of all use-of-force incidents.

This was the context that followed Koby Francis to the McKeesport Police station just before 3 PM on Sunday, December 20th. It was an hour before the shootout. He had been summoned to receive a protection-from-abuse (PFA) order, a type of restraining order for adults or the minor children of adults who suffer abuse by members of their household.

It’s unclear exactly why Francis was served this PFA order, but we know that it covered his four-month-old son and the child’s mother. Just over an hour after Francis left the station, police were called to the sprawling Crawford Village public housing complex adjacent to the McKeesport & Versailles Cemetery. The caller, a relative babysitting Francis’ child reported that Francis was sitting outside the apartment of the person who had obtained the PFA order. Police arrived on scene but Francis had left. They searched the perimeter, and eventually, at the 1500 block of Yester Square, found an upset and combative Koby Francis sitting in a parked car, which they searched before arresting him. Somehow, despite being handcuffed and arrested, police say Francis was able to keep a handgun concealed and move his arms from his back to his front. Officer Athans drove him back to the Downtown McKeesport station—and what followed is, of course, all on video.

Policing has been trotted out over and over again in response to abuse and intimate violence. But, ironically, the literature suggests that police officers are among the most likely demographics to commit domestic violence. The families of police officers are two to four times more likely than others to experience violence at home.

According to the National Center for Women and Policing, “even officers who are found guilty of domestic violence are unlikely to be fired, arrested, or referred for prosecution.” As the New York Times concluded in a 2013 investigation, “In many departments, an officer will automatically be fired for a positive marijuana test, but can stay on the job after abusing or battering a spouse.”

Abolitionist feminists have long argued against policing and prisons as a “solution” to domestic violence. Carceral responses, they argue, represent their own kind of violence, which gets layered on top of already-existing harm, exacerbating rather than alleviating suffering, especially when the victims are femme, of color, and/or undocumented.

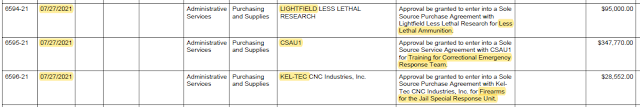

This was all compounded exponentially by police’s heavy-handed and unconstitutional response to Officer Athans’ shooting. Almost immediately after the shooting, a bevy of law enforcement agencies descended upon the Mon Valley: not only McKeesport Police and other small Mon Valley municipal departments, but also the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police; the Allegheny County Police; the Allegheny County Sheriff’s Office; the Pennsylvania State Police; the state Attorney General’s Office; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (BATF); and the US Marshals Service.

This is what residents of Allegheny County are faced with on a daily basis, though many agencies regularly go unseen. The region’s topography and modern history have resulted in a messy, jigsaw-like municipal map that lends itself to over-policing, as jurisdictions overlap, multiplying police presence (particularly in Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela River valley cities like McKeesport). On an average day in McKeesport, you might find not only McKeesport Police in operation, but also the Port Authority Police, Penn State Greater Allegheny Police, McKeesport Area School District Police, the County Sheriff’s Office, the County Police, and officers from the surrounding PDs of Port Vue, Glassport, West Mifflin, Versailles, North Versailles, and others.

Working in concert, at least ten different policing agencies locked down and occupied the city of McKeesport on December 20th. At least four checkpoints were set up, ostensibly stopping every single vehicle attempting to enter or exit the city—on Lysle Boulevard, Walnut Street, the McKeesport-Duquesne Bridge, and elsewhere. SWAT tactical vehicles were posted up Downtown. Police searched home after home, summarily, indiscriminately, searching for a harbored Francis without warrant.

Tanisha Long, the founder of Black Lives Matter Pittsburgh & Southwestern PA and a student at the University of Pittsburgh, happened to be driving into McKeesport on the evening of the 20th to visit with a family member at the UPMC hospital there. But when she attempted to cross the Monongahela River into the city around 6 PM, she noticed something odd.

“There was a long line of cars…which was confusing,” Long tells me. “There appeared to be police officers, so I assumed there was a car wreck, [but] there was not. There were officers looking through windows…Cars were being ushered through. Some cars were stopped, and they were asked to come out the car, open up their trunk. Some people had to take things out of their vehicle[s]. The car in front of me, they made him get out of his car and empty out his trunk. That’s the one I took a picture of…I asked the officer, why are you stopping us? And he wouldn’t answer. And I’m like, what is this search for? And he wouldn’t answer…[The officer] made me roll all my windows down, and they were just looking through [my car]…There were, like, four other points in McKeesport where they did similar things or did a quick search…You couldn’t get through McKeesport. It took me an hour to get to the hospital.”

Fawn Walker-Montgomery, co-founder and executive director at Take Action Mon Valley (TAMV), an anti-violence and community organizing group based in McKeesport, immediately knew something was wrong in her city.

“There were police everywhere in the city. There were over ten police departments. We had the SWAT here, we had the county, we had the state…Just police everywhere, walking around the streets with shotguns…As I rode around, and I went to [Crawford Village], there was people out, so I obviously told them [about] what happened. There were about eight cops just riding through the housing project. So I went home after I seen that, and honestly, I do feel like I was having a panic attack. I came home, and I just did a [Facebook] live, and I said, ‘look, Black people in McKeesport…stay home.’ Because my biggest fear was that they were gonna kill anybody that looked like Koby that night. So, basically, that’s any Black person. I just figured they was gonna kill anybody Black. And as I’m doing this live, I’m getting calls and texts [saying], ‘Fawn, they run up in my house. They pointed guns at my kids. They were just searching the house, looking for Koby.’ This was people who were related to him, people who are not related to him. And I got calls from people [saying]…if you were leaving or trying to come in, they were searching your trunk. And [civilians] would say, ‘well, you don’t have permission.’ And [police] would say, ‘well, you don’t have an option.’ And they would just do it anyway. They were pulling some people out at gunpoint. They were rolling up to people’s houses. They had no warrants. They weren’t even giving people the opportunity to say yes or no. They were breaking some people’s property, they were arguing with some people. They were telling his family, and basically anybody, that they were shooting to kill.”

Until about 4 AM that night, as K-9 units roamed the streets, car after car was arbitrarily searched, and homes were raided, Walker-Montgomery trailed police to document their actions and to connect victims of aggressive police searches with legal counsel and mental healthcare.

She and her organization reached out to contacts at the American Civil Liberties Union, and Pennsylvania Legal Director Vic Walczak quickly slammed police activity in McKeesport, saying, “The shooting of any individual is tragic, but it does not give police license to run roughshod over peoples’ constitutional rights in their effort to arrest the suspect. Now, a day after the terrible shooting of the police officer, it is highly unlikely the McKeesport police can justify continuing the search methods we witnessed yesterday. Warrantless, non-consensual entries into peoples’ homes, suspicionless vehicle stops and searches of motorists’ cars and trunks, and checkpoint stops cannot be justified under the fourth amendment to the U.S. Constitution or Article I, section 7 of the Pennsylvania Constitution.”

Nothing justifies police violating the 4th Amendment by searching vehicles and homes without probable cause and without a warrant. Read our statement on the actions of McKeesport police by our legal director, Vic Walczak.

The testimony that TAMV has collected on these illegal police actions—including the accounts of 18 victims and eyewitnesses—are likely to form the basis of class-action litigation against the agencies involved. Walker-Montgomery tells me she instructed terrified civilians to comply with police searches that night, fearing that any altercation could lead to more violence. “‘Don’t argue with [the police], just let them [search], because I want you out alive,’” she remembers telling people over the phone. “And they’re saying, ‘well, do they have rights to do this?’ No, they do not. But at this point, we gotta decide if we’re going to argue with them, and possibly die, or just let them [search]…Being in that position is very traumatic, because you know you have rights, but you know if you use those rights, if you bring them up, you could die.”

Brooke Harris, Francis’ cousin, told reporters that her and her mother’s home were searched without warrant within hours of Athans’ shooting. “They opened up the door [to my mom’s house]. The babies were standing right here. They opened up the door and they had the guns aimed…they [pushed] my mom and my uncle out of the way, who are both elderly in their 70s, and charged upstairs,” she said, and added that when they searched her own house across the street, police damaged her closet and pulled some curtains down before tossing them in a baby’s crib.

Responding to community criticism of the unconstitutional and aggressive searches, Allegheny County Police superintendent Coleman McDonough said, “I just find it hard to believe that we’re talking about these issues when Mr. Francis is still out there in the community, endangering innocent citizens…I think that’s the priority that we ought to be talking about today.”

But is concern about harm coming to the community of McKeesport really moving the police here? Their drastic, martial response seems more connected to the fact that the victim was a police officer rather than the actual substance of the crime. A Black civilian being shot is part and parcel of the system of policing to which McDonough belongs. But a Black civilian shooting a police officer? The full force of police’s violence work must be felt.

Police/(para)military occupations are carried out when state regimes feel they must consolidate their monopoly on violence. That is what the McKeesport crackdown was about.

If they cared so much about community harm, where was all of this action in late May 2020, when 32-year-old Black transgender hairstylist and ballroom emcee Aaliyah Johnson was found dead outside her apartment on Sinclair Street in Downtown McKeesport? It took grassroots movement builders like Dena Stanley of Trans YOUniting to get the public eye on Johnson’s case. What about when George Brosey was found shot to death at Crawford Village in June? What about Niko Dawson, 31, or Keith Jones, Jr., 20, both murdered in July? Officer Athans is thankfully still alive today. A lot of McKeesport residents can’t say the same about their loved ones.

Walker-Montgomery shares my suspicions here, that the police’s response to the Athans shooting was not only disproportionate, but cynical. “[The police response was] just further confirmation of what we already know about police. They’re violent. They have a strong blue line, to where they really care about their own,” she says. “There are a lot of shootings in McKeesport. A lot. On a weekly basis. There have been triple homicides, double homicides in this city. People have died, children have died, parents have died, mothers, fathers, brothers, uncles, cousins. And we have never had that many police resources in our entire lives. I know families, including my own, that would kill to have that many resources available to get justice for their loved ones. It made me sick to my stomach…You have people over here who’ve been waiting for justice for ten years plus for their loved ones, and weren’t able to have that kind of attention.”

Within a week, four more young adults between 19 and 25 years old were charged with hindering apprehension for allegedly helping Francis to escape after being seen on CCTV footage entering a convenience store and riding in a car with Francis after the shooting.

Shortly after Athans’ shooting, the BATF had put up a $10,000 reward for tips leading to Francis’ arrest, which was followed up by an additional $5,000 from local automobile dealer Richard Bazzy, putting a $15,000 bounty on Francis—and on December 29th, after nine days on the run, an anonymous tipster called the US Marshals Service with knowledge that Francis was hiding out at the Oakmound Apartments in Clarksburg, West Virginia (a city anchoring the southern portion of the Pittsburgh megaregion). Police entered the apartment where Francis was staying by himself, unarmed. “He was actually asleep when we came in and arrested him,” Chief Deputy Terry Moore of the US Marshals Service said, suggesting Francis was arrested via no-knock warrant (a strategy that has been decried by lawmakers and activists since Breonna Taylor’s assassination). Lieutenant Venerando Costa of the Allegheny County Police said in a press conference that Francis’ arrest had been carried out by the Northern Office of West Virginia’s Mountain State Fugitive Task Force in an interjurisdictional collaboration with at least twelve policing agencies—McKeesport Police, Allegheny County Police, the Allegheny County Sheriff’s Office, Pennsylvania State Police, the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, West Virginia State Police, the US Marshals Service, the BATF, the FBI, the Harrison County Sheriff’s Office, the Clarksburg Police Department, and the Greater Harrison County Drug and Violent Crime Task Force.

On Friday, January 8th, the Allegheny County Sheriff’s Office successfully extradited Koby Francis back to Pittsburgh. Allegheny County Sheriff’s deputies shuttled Francis from the North Central Regional Jail in rural Doddridge County, WV to the Allegheny County Jail in Downtown Pittsburgh.

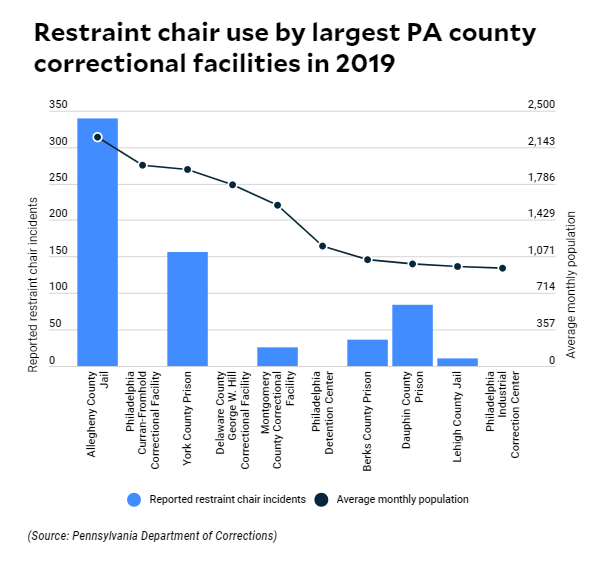

Both of these facilities are death traps. In 2019, the West Virginia Division of Corrections was sued by the mother of inmate Zachary Bailey, who died under disputed circumstances at North Central just a few weeks after Janson Davenport was found dead in his cell there. Then, in December 2020, two inmates at North Central were pronounced dead after being found unresponsive in a quarantine cell. And at this point, Allegheny County Jail (ACJ) can no longer hide its medical neglect, excessive force, abuse of the mentally ill, unsanitary conditions, and staggering suicide rate. Timothy Pauley died at ACJ in April 2019 after a suicide attempt, Daniel Pastorek was found dead in his cell there in November 2020. And on top of all this normalized violence, we are in a pandemic, and detention facilities are superspreading factories for the coronavirus.

Koby Francis is at ACJ until further notice. On Tuesday, January 12th, 2021, he was denied bail by Allegheny County Common Pleas Judge Edward J. Borkowski. His preliminary hearing, scheduled for today, January 21st, was postponed until mid-February.

The entire Francis-Athans debacle was precipitated by a single interaction between officer and civilian. In our abolitionist future, this type of interaction wouldn’t happen again.

What if this whole situation—the PFA order, the violation—had been given over to a talented social worker, of which Allegheny County has many? The situation—Koby Francis sitting in a car outside the apartment of his alleged abuse victim—was potentially disturbing, but it wasn’t an emergency that required armed personnel to respond. What if a local social worker had had an existing relationship with Francis, allowing them to effectively step in and de-escalate the situation?

How can we transform harm? That is the question we keep coming back to. As abolitionists, we are animated by a hunger for healing, not retribution. Justice means nothing if it does not transform the original conditions from which harm emerged.

When a contingent organized by TAMV tried to call all of this out at the McKeesport City Council meeting on the evening of January 6th, they were barred from entering. Fawn Walker-Montgomery says that the group, about eight strong, had signed up for speaking slots through all the proper channels—but when they arrived, they found a note on the door indicating that the meeting was closed to the public due to the coronavirus. Though they could see civic officials carrying on a meeting inside, this group of residents was literally locked out. Walker-Montgomery says this was in direct violation of Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act, a statute which guarantees the right to witness open governmental proceedings, holding that “the right of the public to be present at all meetings of agencies and to witness the deliberation, policy formulation and decision-making of agencies is vital to the enhancement and proper functioning of the democratic process.”

The City Council has another meeting coming up on Wednesday, February 3rd at 7PM. Walker-Montgomery is asking all who are able to call, message, and email McKeesport City Council, and show up to their February meeting to be heard in person.

Contact McKeesport Mayor Michael Cherepko. Contact McKeesport Police Chief Adam Alfer. Contact Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala, Jr.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

Suhail Gharaibeh is a Chicanx and Arab American writer born and