by Autumn Redcross, with Man-E of Bukit Bail Fund

Bail is a contract. Bond is the fulfillment of bail. The agreement of bail is the temporary release of someone who has been accused of and/or charged with a crime. Although it does not have to be, often bail is indicative of a financial exchange. In that sense, bail is the amount of money defendants must post to be released from custody until their trial 1. But, there is also bail through non-monetary means, such as electronic monitoring and release on own recognizance (ROR). Unsecured bail carries a dollar-amount, but not needed at the time of release.

The purpose of bail is to provide a means out of detainment and is meant to insure a defendant’s appearance at pretrial and trial hearings for which their presence is required. With that in mind, the cost of monetary bail is returned once the accused person shows-up for their trial. However, no-shows mostly results in a forfeiture of bail monies. Moreover, the full amount of an unsecured bond is due from the individual charged fails to attend their hearing.

Not meant as a fine or form of punishment, the 8th amendment to the constitution promises protection from cash bails set too high to meet for anyone accused of a crime. Clearly stated, “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”2 However, our states fail us by conforming to strict bail requirements for the release of unheard citizens. Bail impositions greatly contribute to the state of mass incarceration: the prison-industrial complex today.

In 2011, critical race theorist Michelle Alexander published The New Jim Crow – a powerful and damning portrait of the impact of the prison-industrial complex on the lives of people of color in the United States. While the U.S. represents about 4.4% of the world’s population, it houses around 22% of the world’s imprisoned people. Not only those confined to prison, but also those on probation, parole, immigration detainment and local jails. Five years after the publication of her book, 2.3 million people were still incarcerated in the United States.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 35% of state prisoners are white, 38% are Black, and 21% are Hispanic/Latino3. Although Black and brown people make up a minority of the US population, “African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at more than five times the rate of whites, and at least ten times the rate in five states.”4 Alexander illuminated the staggering observation that more Black men were behind bars or custodians of the criminal justice system during the time of her writing, than were enslaved in 1850. Bail is the threshold to this phenomenon.

Prior to the onset of coronavirus, it was said that, “on any given day” there are about a half million people sitting in jails of which the majority are there because they cannot afford the bail monies set for their release5. Accused – but not found guilty – lawfully innocent people are arrested and detained with gross regularity across the country.

To quote the Prison Policy Initiative, “Six out of 10 people in U.S. jails—nearly a half million individuals on any given day—are awaiting trial. People who have not been found guilty of the charges against them account for 95% of all jail population growth between 2000-2014.”6 63% of those in jail have not been convicted” and sit as pre-trial and unconvicted members of the jail population, despite their innocence.7

The presumption of innocence fails in the face of monetary bail. Because cash bail inherently disenfranchises the poor, it is the marginalized populations within our society who are smothered by the stigma of accusation and further impoverished by the price of justice. For the wealthy, bail may be an unexpected inconvenience. For others, bail is debt bondage.

“How much is your freedom worth?” the words of spoken word artists ring out when hearing from the sales pitch of the bondsmen.8 The artistic piece produced by Brave New Films features the experienced arrest, detainment and the option for bail. Days of jail time can mean loss of employment, housing property and relationships. The stigmas associated with being in jail runs deep. “Because even a brief period of pretrial detention can have a devastating impact on the person jailed” all of the trauma produced, is caused despite presumed innocence.9 Therefore, innocent people in jail and their families are often forced to seek the assistance of a bail bondsman.

Bail bondsmen profit from the criminal justice system. The bondsmen target the poor, as only those who cannot afford cash bail need to use their services. The United States and the Philippines are the only countries that allow for-profit bail companies. Charging only a percentage of the bail cost, bondsman companies post bail that is not refundable to the accused even once they show-up at court. Yet, payments to the bondsman continue until the debt is fulfilled.

Despite the findings that the cost of bail does not determine a person’s appearance in courts. Instead, an exceedingly pragmatic and much cheaper reminder of an upcoming court date is found to be much more effective.10 Cash bail continues to be demanded by the courts of Pennsylvania, and is thereby a capitalist strategy for perpetual arrests, and continued detainments of Black, brown and poor people in Allegheny County.

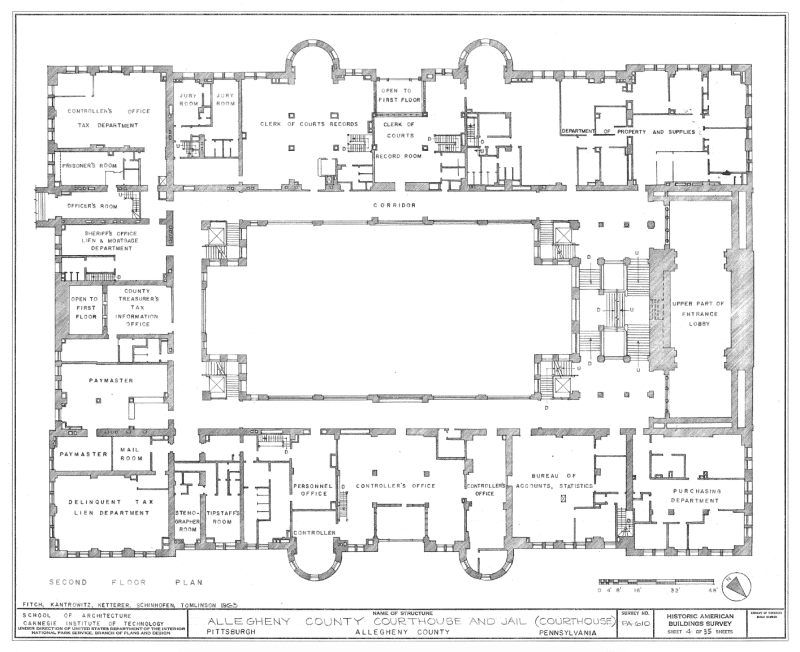

Until recently, about 20% of the ACJ population was held as pretrial detainees according to the 2016 Criminal Justice task force report. The Jail Stats Report dated May 15th shows that “22% (285) of people in the jail itself were held pretrial-only, meaning they had no other reason (such as external holds or detainer) keeping them in the jail. Of these people, only 2% were screened as low risk for re-offense based on the Allegheny County locally validated pretrial risk assessment (without consideration of the seriousness of the current offense). The report cites that only 86 individuals (approximately 7% of the jail population) are currently being held in the Allegheny County Jail pretrial-only on monetary bonds. Of these individuals, only 5 screened as low risk for new criminal activity, and all 5 of these individuals were facing charges for violent offenses.”

“Arrest is kidnapping: bail is ransom.” This is the fundamental conviction of Man-E, and the motto of the Bail Bukit Fund which calls for the end to cash bail in Pittsburgh and everywhere else the practice exists. Abolitionists at heart, Bail Bukit Fund believes that no one should be caged. Impassioned by the loss of Frank ”Bukit” Smart, who died when restrained during a seizure at ACJ, the Bail Bukit Fund fights for the abolition of all jails and freedom for those ensnared by it.

Man-E knows its trappings well. He’s been arrested and detained three times, but has never been found guilty of either charge.”The whole system is really unfriendly and biased,” he says.

Man-E was a teen at his first arrest with no prior charges. “I was arrested with a co-defendant, his bail was $5,000 and mine were $25,000. Guidelines of fairness are not adhered to. He was on probation and should have been deemed as a more serious case than I was. But who is to say how the judge was thinking at the time.”

The second arrest led to the same $25,000 cost set for bail. Yet the third was double that amount. Man-E tells the story. “In my case we went to a bail bondsman, they charged us a percentage and my mother put-up her house.” There was no other way to pay the bond set for him. Although he had no prior convictions, Man-E was denied a bail reduction. He explains, ”I had previous charges, but no convictions despite being innocent before proven guilty.”

The $50,000 had to be paid through the bail bondsman. “To stay in jail and essentially get punished without even being tried. I was acquitted 2 years later. And yet, he says, “There is no reconciliation for the time or money spent.” Had he remained in jail for that amount of time, “I would have lost my job and possibly my house. Some lose custody of their children. Some die,” he added.

“Cash bail and really doesn’t serve the intended purpose but serves to make as much money as you can, not only for the courts but the bail bondsman. When the case is resolved,” he continues, “they get the money back plus the percentage. And had I not shown up, they would have got my mom’s house as well.” He says further, the bondsman company did not return their asset as eagerly as they had taken it. “They did not contact us to return the deed, we had to go to him.“

“In all of my cases I was found not guilty, but was treated as if I was simply because I was charged. The system overall is flawed even though it’s been here so long, most cannot imagine it any other way. Cash bail itself shouldn’t have a place in our criminal justice system. If a person is dangerous, the only thing that prevents them is how much money they have.”

“There are a lot of things wrong with the criminal justice system, but most people would agree that pre trial detention is one of the most egregious. It punishes people despite the presumption of innocence.” From his experience and what he has seen, Man-E contends that the trial process in “Allegheny county takes so long, they plead out to get time served, and hope to get out on probation.”

Man-E shares that the conditions at ACJ are often seen as worse than any Pennsylvania State Penitentiary.

“The first time I was there, I was 16. I saw someone get knocked out. The CO saw and didn’t say anything. I’m a vegetarian and they didn’t care. They charge ridiculous amounts of money to speak to your family. They give you just enough to survive. There is no dignity” there, he says.

“A social worker told me that they make it as bad as possible so that you will not want to come back. They don’t treat you like a human there,” he said. But what he wants to share, a message of hope for those confined in jail. ”They weren’t there their entire lives, they won’t be there their entire lives.”

“There are a lot of people who are victims who do not know that people care about them. The whole experience is disheartening and some have a hard time coping even when they are released. Some cannot cope at all and begin to take drastic measures. People are aware, care and are working to make a difference.”

“Bail reform is a civil rights issue. Bail reform is a human rights issue. Bail reform is a national crisis that’s hidden in plain sight” – Wade J Henderson

Whether in need or in want to support the movement to abolish cash bail in Allegheny county and beyond, please visit bukitbailfund.org.

Notes

- https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/resources/law_related_education_network/how_courts_work/bail/

- The 8th Amendment to the United States Constitution

- https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

- Brave New Films documentary, Breaking Down Bail

- https://www.pretrial.org/get-involved/learn-more/why-we-need-pretrial-reform/

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/pretrial_by_state.html

- https://vimeopro.com/user49077866/bailtrapseries/video/252377674

- https://iop.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/Reports/Status_Reports/Criminal%20Justice%20in%20the%2021st%20Century%20-%20Improving%20Incarceration%20Policies%20and%20Practices%20in%20Allegheny%20County.pdf

- https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/234370.pdf

- https://iop.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/Reports/Status_Reports/Criminal%20Justice%20in%20the%2021st%20Century%20-%20Improving%20Incarceration%20Policies%20and%20Practices%20in%20Allegheny%20County.pdf