Mass incarceration and the adverse collateral consequences of criminal prosecutions and convictions are deeply entrenched in Allegheny County, PA.

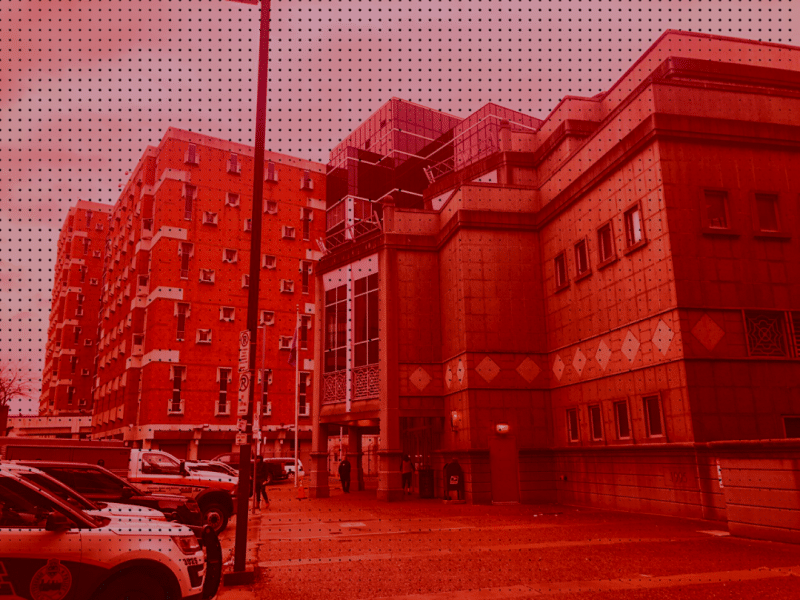

More than 80% of those held in the Allegheny County Jail (ACJ) are not serving a sentence for a criminal conviction but instead are held pre-trial or on alleged probation violations.

More than half of those held in ACJ are being held pending resolution of probation violations, which are often technical violations that do not involve a new charge.

The County has a higher incarceration rate of Black people than the national average.

While only 13% of the County population is Black, approximately 50% of those held in ACJ are Black.

MAY 20 – SNAPSHOT

Lack of Testing in ACJ Will Fuel the Second Wave

District and common pleas courts feed and maintain the Allegheny County Jail (ACJ) population. People detained there become subject to the care of the county, their health and wellness jeopardized by the negligence of elected and anointed officials. ACJ governance is refusing to adopt a platform for universal COVID-19 testing and is now reporting data as if the jail is coronavirus free.

Here is what’s been recorded:

| The ACJ population | 1668 |

| Number of individuals tested | 65 |

| Number of Negative results | 35 |

| Number of Pending result | 2 |

| Number of Positive results | 38 *1 hospitalized |

| Number of COVID-19 positive people who have recovered or been released from ACJ | 28 |

| Number of COVID-19 positive people remaining at the ACJ | 0 |

Throughout the nation, jails and prisons are reporting staggering numbers of COVID-19 outbreaks. Philadelphia County Jails were found to have 75% of their population testing positive for coronavirus, and will now integrate universal testing at their jails.

Allegheny County insists on a test-less methodology shown in their failure to pass a motion for universal testing. By Wednesday this week, only 65 out of the 1665 detained individuals have been tested for coronavirus. This constitutes a %.04 testing rate of the people detained at ACJ; less than ½ of 1% of the ACJ population has been tested. 3 new tests have been given this week.

The county jail is not a vacuum, but has workers, staff services, PO’s and CO’s, etc., filing through on a regular basis. Long and short term destined people are vulnerable to unsanitary conditions and contracting the virus. Rather than moving decisively forward with an interest in our public health that aims to overcome the current crisis and divert the threat of a second wave, authorities are failing to protect lives by testing widely.

We support Councilperson Bethany Hallam’s motion for universal testing for county-run facilities and urge the council committee, under the leadership of Councilperson Olivia “Liv” Bennet, to test all people under county care.