FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT: Andy Hoover, ACLU of PA, media@aclupa.org

William Lukas, Abolitionist Law Center, wjlukas@alcenter.org

Jonathan de Jong, Institute for Constitutional Advocacy & Protection, reachICAP@georgetown.edu

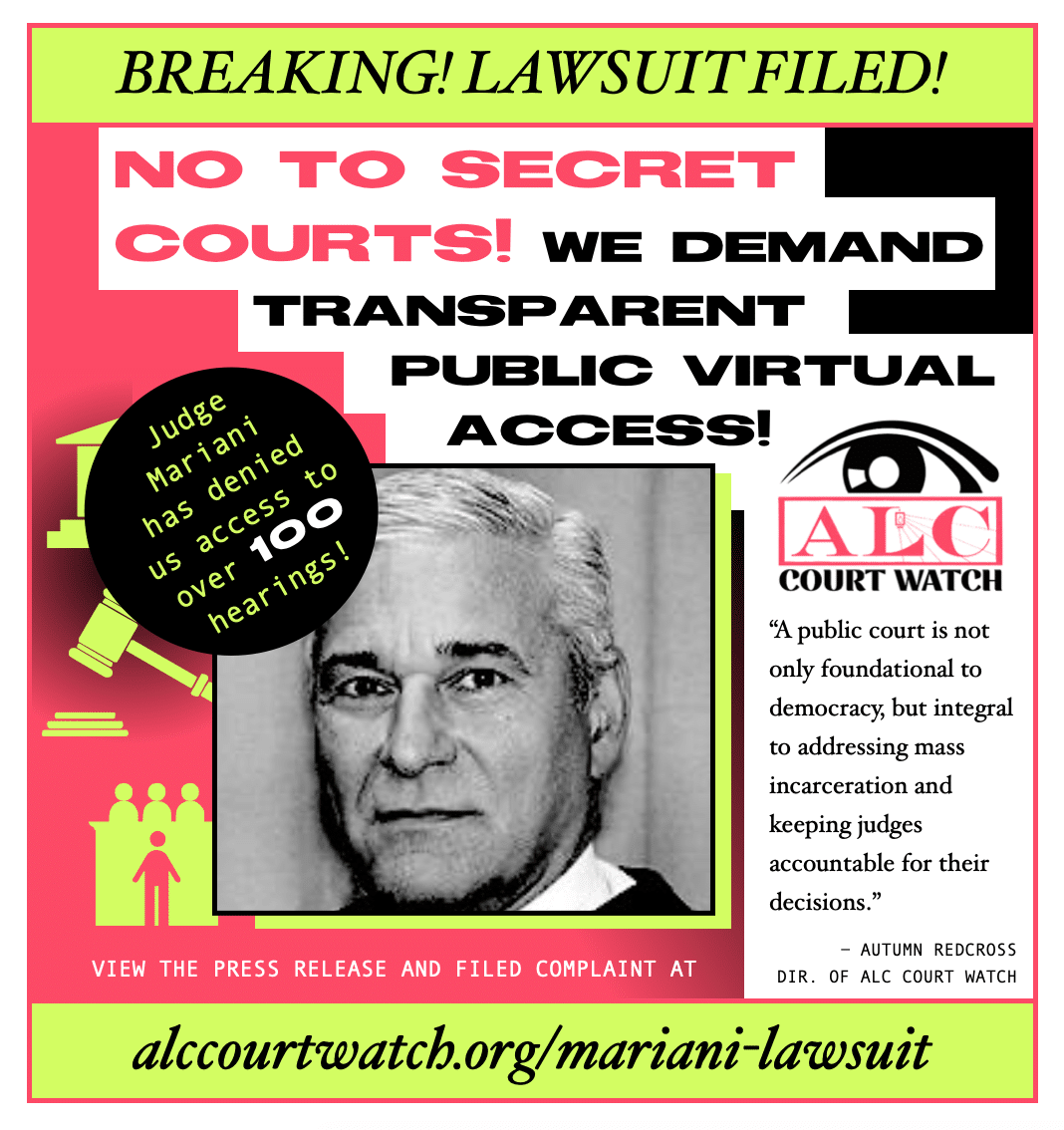

PITTSBURGH – An Allegheny County judge is facing a federal constitutional lawsuit filed today by Abolitionist Law Center after the judge’s refusal to allow virtual access to his court proceedings. Judge Anthony Mariani has repeatedly denied online access to volunteers with ALC’s Court Watch program and has only allowed the public to observe his court’s hearings in person at the county courthouse, despite a directive from both the court administration and the state Supreme Court that judges should provide online access to the public as a COVID-19 mitigation strategy.

Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania and the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University Law Center, ALC argues in its filing that public access to courts is a First Amendment right.

“A public court is not only foundational to democracy, but integral to addressing mass incarceration and keeping judges accountable for their decisions – many of which are racialized and have contributed to apartheid in Allegheny County,” said Autumn Redcross, the director of ALC’s Court Watch program. “In the midst of a year-long global pandemic that has disproportionately devastated Black and brown communities, it is not sufficient to say, ‘the courts are accessible,’ simply because the buildings are open.

“It is unethical to expect community members to risk their health and lives to show up in person to observe an alleged public hearing, when the judge can provide the public with remote access.”

Since January, ALC volunteers have requested access to more than 100 hearings, all of which have been denied by Mariani. Typically, those asking for access receive a form email that states that the public can observe hearings in the judge’s courtroom. But in February, Mariani’s chambers stopped replying to inquiries by ALC’s volunteers as to why they could not have virtual access.

Mariani is the only Allegheny County judge who has refused to grant access to hearings via online video conferencing, in all his cases without exception. In its complaint, ALC notes that nine court employees tested positive for COVID-19 between January 10 and February 10 and that all had visited court facilities, including one member of Mariani’s staff.

“We jump through all the hoops set up by the Fifth Judicial District for safe, remote access, but, instead of access, I get form emails denying me and telling me to attend in person,” said Erica Brusselars, the volunteer coordinator for ALC’s Court Watch program. “Judge Mariani is actively obstructing safe public access to his court. He is impeding transparency in a way that hurts public discourse, hurts our tradition of open courts, discourages an engaged citizenry, and blocks people from seeing our criminal legal system.”

“Courts operate openly, not in secret, and this judge cannot be allowed to escape scrutiny while refusing to implement common sense strategies to prevent the spread of COVID-19,” said Reggie Shuford, executive director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

“All courts must be open, and the stakes couldn’t be higher than in criminal court, where judges make critical decisions that impact people’s liberty and freedom,” said Nicolas Riley, senior counsel at the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection.

In its filing, ALC is asking the federal court to require virtual access to Mariani’s proceedings, for a ruling that his behavior is in violation of the First Amendment, and for attorneys’ fees and costs.

The lawsuit, Abolitionist Law Center v. Judge Anthony M. Mariani, has been filed in the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania. ALC is represented by Witold J. Walczak and Sara J. Rose of the ACLU of Pennsylvania and Nicolas Y. Riley, Robert D. Friedman, and Jennifer Safstrom of the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University Law Center.

A copy of the complaint filed today is available for download below and also available at aclupa.org/ALC.